A project that seeks to explore the cultural significance of hair (both its presence and absence) by investigating its uses in contemporary visual culture.

What you will find here is number of works discussed with larger visual cultural context in mind. I attempted to organise them under certain keywords, but they are often interrelated in more ways than anticipated. You might therefore find an installation discussed together with a photograph or a film together with a performance. You might also encounter the same artists in different sections, since what is of interest here is not focusing on specific disciplines or artists but to see what all this tells us about our visual culture and the significance of hair.

HAIR

COVID 19 Note

My interest in all things hair related started before it even became a project. Recently, I have been trying to develop a more structured approach to the existing material, and conversations -images, newspaper articles and other- material I accumulated over the past few years.

Bulk of the work for this web project was done during the lockdown. I could not possibly envision that hair would become central during lockdown, yet most people, who knew I was working on hair, sent me something related to lockdown and hair. In certain parts of the world demanding hair dressers to open was a legitimate reason to protest.

Hair dresser conversations, state of our hair and the need to visit a hair dresser, was in the background while I was trying to organise my thoughts about how to map out centrality of hair in our lives. However, the murder of George Floyd, and the protests that followed worldwide, was another part of the background. Hair, as I will try to illustrate, is a large part of how we form our opinions and biases about people. Racial, ethnic, religious discrimination relies, among many things, on our perceptions of how hair looks and whether it is visible or not. With that in mind this project wants to look at hair in visual culture, making connections between seemingly separate works and conversations, that are in fact responding to how much hair organises our lives.

Why Hair?

Coming from a culture where curly hair is, not necessarily always appreciated but very common, it was in Britain I first encountered the phrase “Jewish hair”. It was also here that I found out hair dressers could not necessarily cut my hair the way I wanted. I was told my hair texture was “different”. My hair, I thought, was very common, slightly wavy thick hair, yet hairdressers were not familiar with it. Around the same time, I noticed how segregated hair dressers are in Britain, not just based on class but also race and ethnic background. There are “salons”, middle eastern hair dressers, black barbers and so on.

Becoming more occupied with hair, I discovered art works on hair, watched documentaries, feature films and TV shows entirely or partly about hair and noticed how much it says about different cultures, how big a role it plays in how we perform ourselves and how central it is in the way we discriminate against others.

Hair is manipulated, shaped, collected and traded. It says so much about us yet we speak so little of it in our discussions of art and culture. As Kobena Mercer states in a much-quoted article, hair is “never a straightforward biological ‘fact’ because it is almost always groomed, prepared, cut, concealed and generally ‘worked upon’ by human hands. Such practices socialize hair, making it the medium of significant ‘statements’ about self and society and the codes of value that bind them, or don’t” (Mercer, 1987: 34).

Hair and Visual Culture

Hair means care, hair means race, culture, it means resistance, and it is punishment, it is sculpted to be displayed and it is sacred and to be shielded. It is private and intimate but also public and (still) political.[1] It is also a huge industry, not just through products that we buy and sell but also because hair itself is bought and sold (Emma Tarlo explores this in fascinating detail in her book Entanglement: The Secret Lives of Hair).

Hair is also important in many religions and considered sacred in many cultures. Most practicing Muslim women believe their hair should not be visible in public, so do Sikh men. Orthodox Jews have different practices regarding hair for men and women and Native Americans protect their hair as they believe it gives them power, connects them to nature and is sacred. Hair also contains information about us, it carries our DNA. It is part of our identity and often considered something to do with how attractive one is. Yet once it falls off our head it is deeply uncanny. This aspect is also explored often in art by artists such as Mona Hatoum and David Hammons, albeit differently. That uncanny nature of hair when out of place, changes when re-placed. Many cultures keep hair locks as memorabilia. In Victorian Britain, for instance, hair was used in mourning jewellery. Objects containing the hair of the deceased were designed to be worn.

Credit: Brooch containing human hair, Europe, 1701-1900. Science Museum, London. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Any work that wants to explore hair could do so by looking at any one these different areas. Only to look at the economic aspect would be a huge undertaking. What this project is interested in is hair in visual culture (which, as the recent reaction I received summarises, “is [also] huge”). However, I am less interested in mentioning/examining every single major work on the topic, and more interested in looking at dialogues, connections, conversations between works that are about hair. Although works themselves might be endless in numbers, the concerns and conversations are not.

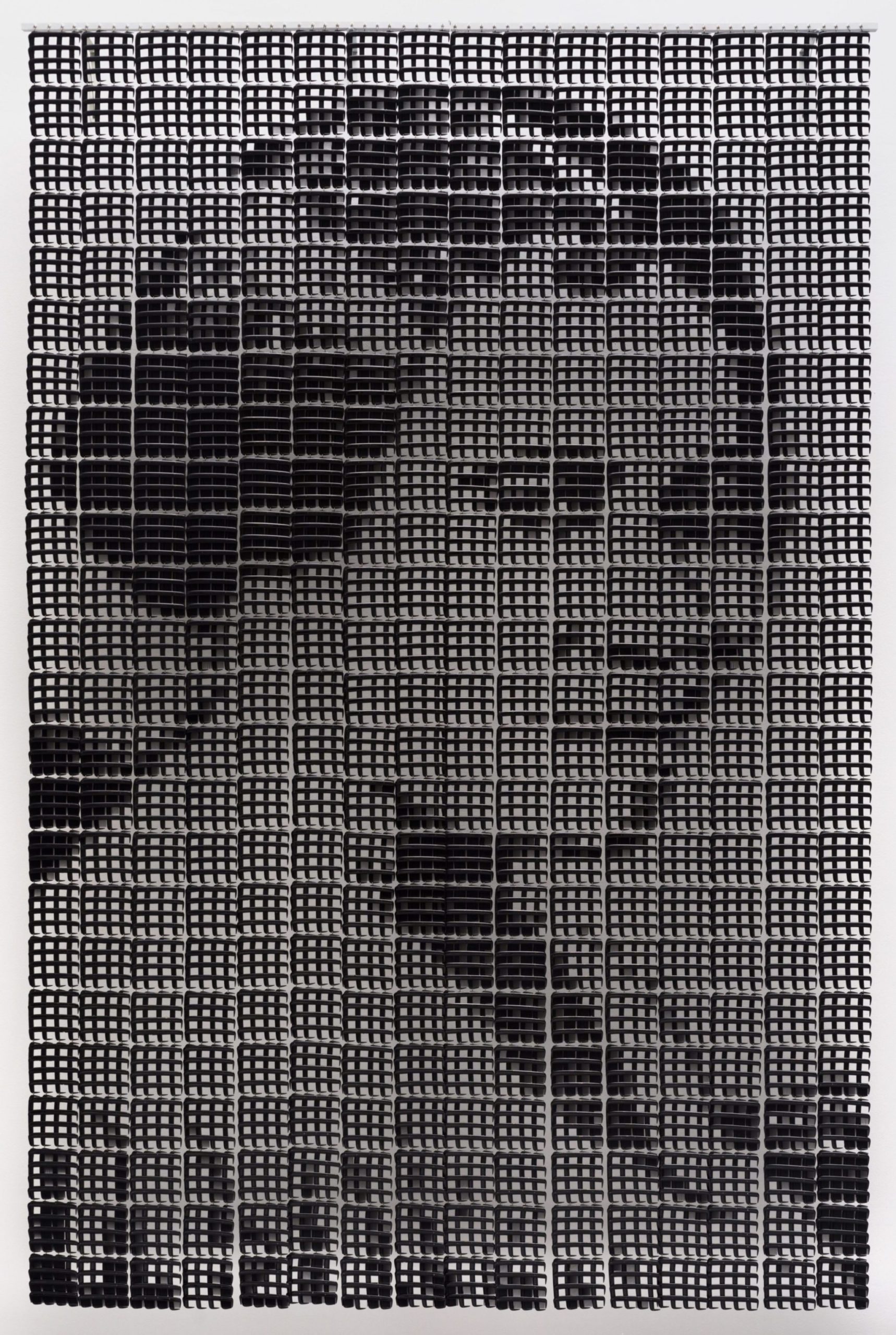

(from the Exhibition Rock my Soul, Victoria Miro, Curated by Isaac Julien)

Photo Credit: Ozlem Koksal

How to Define Visual Culture

I take Nicholas Mirzoeff’s definition of visual culture as my guide here, which focuses on “creating and exploring new archives of visual materials, mapping them to discover connections between what is visual and the culture as a whole” (2015:14). In that sense, this web content, a curated collection of hair in visual culture, seeks to begin creating one such map that is curious about those connections and meanings. By mapping them out, I seek to see how art and culture respond, perform and subvert or reproduce existing discourses and practices regarding hair.

As Mirzoeff points out “visual culture is not simply the total amount of what has been made to be seen […]. A visual culture is the relation between what is visible and the names that we give to what is seen” (11). This is why it is important to understand these connections as well as looking at efforts to subvert them. Where do these names come from, who named them and why? And more importantly, how much of it still determines our perception even though –or because- we forgot where they come from.

Norms that structure societies, that are created arbitrarily, also create deviants. Yet it is the norm that needs to be questioned, examined and de-normalised -not what’s left outside of it. Art does this. Talking about difference, Stuart Hall says that “if you want to learn more, or see how difference operates inside people’s heads, you have to go to art, you have to go to culture – to where people imagine, where they fantasise, where they symbolise. You have to make the detour from the language of straight description to the language of the imaginary” (Hall, 152). It is my aim here to examine those cultural productions with the intention to connect the concerns and questions they raise, with an attempt to “deconstruct colonised imaginary” (Hall, 152).

How to Contextualise Hair?

How do we understand our existing perceptions and ideas of what hair represents and what it means?

There are many instances that hair is not just hair. It is performative and political. How it looks (or whether it is visible or not), as well as its absence/loss is never straightforward. Audre Lorde, for instance, writes about how her dreadlocks caused her to be denied entry into British Virgin Islands. A decision went beyond unwritten rules that regulate our lives, as this was actually written into the law. For years, there has been a debate on whether veiled hair should be allowed in schools and public spaces in secular countries such as Turkey[2] and France. When the first female MP with a headscarf entered the Turkish parliament, it was a politically significant, and highly charged, moment in the country. Similarly, when Iranian women started removing their head scarves in public spaces in 2014 it was equally political, going beyond demanding oppression to end.

In Budhism shaving hair is sign of devotion and humility but is also required because it is considered ‘dirty’. In the 50s, in Kenya, on the other hand, it served as a highly political statement as Mau Mau fighters did not cut their hair.[3] Similarly, Angela Davis’ afro hair during her court appearance in 1971 was not just about ‘going natural’, it was an immensely political act. Yet, it is also important to note that how Davis’ Afro became an iconic image is as political as the initial act itself. In her autobiography Davis notes that “It is both humiliating and humbling to discover that a single generation after the events that constructed me as a public personality, I am remembered as a hairdo. It is humiliating because it reduces a politics of liberation to a politics of fashion; it is humbling because such encounters with the younger generation demonstrate the fragility and mutability of historical images, particularly those associated with African-American history” (xv). Because hair is highly charged and says so much about us, it is also used to subjugate us. After 2nd world war, when some French towns decided to publicly shave the hair of those women accused of collaborating with Nazi’s, it was a political act as well as a punishment, an a highly gendered one. A form of punishment reserved for women that goes back centuries. Cutting someone’s hair without their consent is a form of punishment that has a long history and is directly related to political and cultural capital.

As the examples illustrate, hair –among other things- is very much entangled with identity politics, as well as cultural rituals. Therefore, it is not surprising that hair continuously appears in visual culture, from films to art works. This, in cultural realm, manifests itself in art works using real hair, or made about hair, films and television shows entirely on hair, episodes and segments that are about hair, book chapters, stories and poems written on aspects of experiences determined simply by how one’s hair looks. Works of David Hammonds, Sonya Clark, Lorna Simpson, Mona Hatoum, along with many others, consciously and repeatedly use hair in their works. Yet, this is not just visible in art, it is there in popular culture too.

My baby sister was into it. #HairLove pic.twitter.com/AztL0ZoNLv

— Vote Early & In Person (if you can) (@JazminsThoughts) December 7, 2019

Photo credit @JazminsThoughts (Twitter)

In the 2001 film Believer (Henry Bean) a group of Neo-Nazis men go to a kosher restaurant. They mock the waiter’s curly hair: “look at his hair” “who does your hair?” one of them says. The commentary on hair in Believer subtle and tangential -a way to mock the waiter’s Jewish heritage. Yet there are also many films that are exclusively about hair. In the Venezuelan film Pelo Malo (2013) director Mariana Rondon tells the story of a nine-year-old Junior who becomes obsessed with straight hair as he tries everything to make this curly hair straight. The film gives us a glimpse of Venezuelan race relations as well as class by simply following Junior’s struggle with his hair.

More recently, in 2020, Matthew Cherry’s short animation Hair Love about a little black girl and her hair, won the best short animation Oscar and received much attention. In 2018, hair styles in Black Panther was discussed by many. Articles appeared focusing solely on the hair styles in the film, discussing how the film was a showcase for natural hair and how hair was used to create the world of Wakanda. One of the most iconic scenes in the film is when Danai Gurira’s character Okeye throws her wig at her opponent, not only violently rejecting what was imposed on her to “blend in” but also using it as a weapon, as it momentarily blinds her opponent. Perhaps one of the best examples illustrating how otherwise very different works (speaking different languages to different audiences) are in fact connected can be found in the 2020, Netflix series Self Made. The series tells the story of one of the first female American philanthropists, Madam C.J. Walker, who made a fortune by creating hair products for black hair. Madame C.J Walker was also the subject of a portrait by Sonya Clark in 2008, made out of 3840 fine toothed pocket-combs.

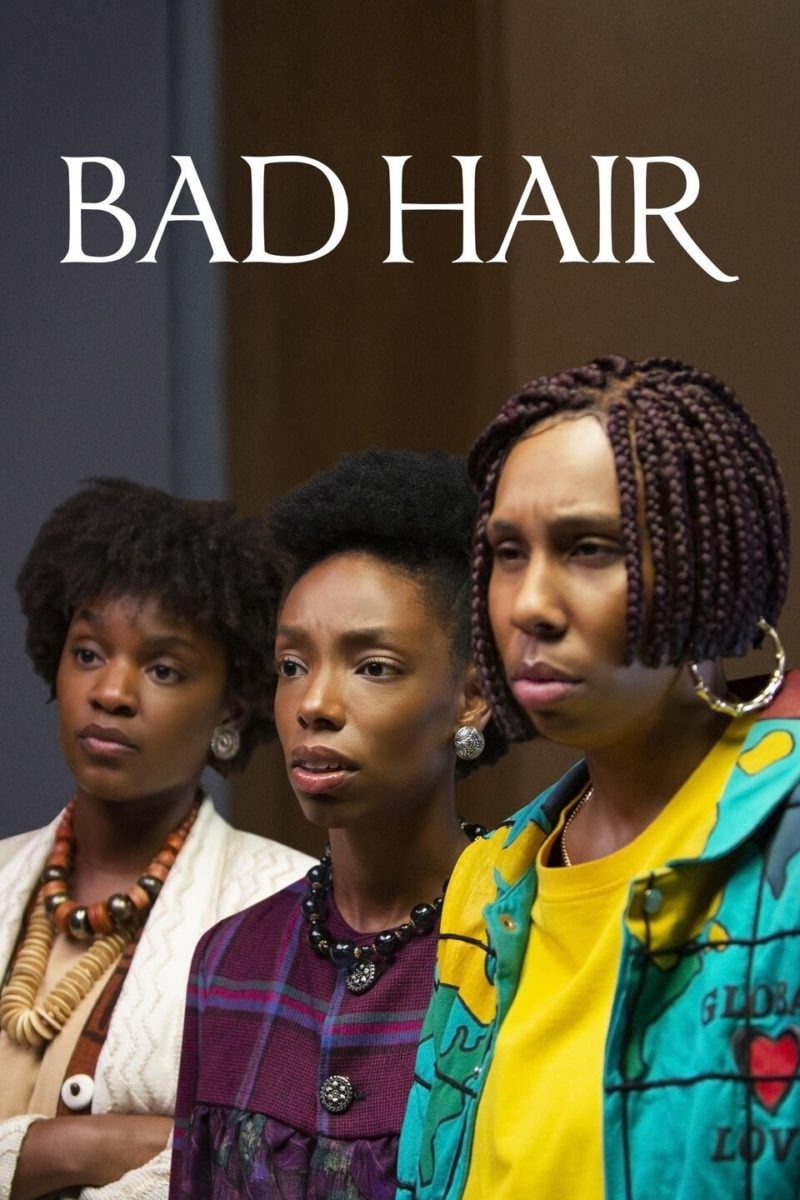

Recently, a comedy horror film Bad Hair directed by Justine Simien premiered at Sundance film festival in January 2020. The film is set in the 80s and tells a story of a woman and her weave that is (literally) evil. Bad Hair is the most recent addition to films that look at race and beauty standards imposed by the West. It is also the newest addition to the long list of films that use hair as an element of horror such as Exte (Sion Sono, 2007), The Ring (Hideo Nakata, 1991) and The Wig (2005, Won Shin-yun).

Hair as Discriminant

There are many different practices, historic and contemporary, where hair is directly used to classify, and even punish, people. Some of these are unwritten rules and expectations, and some are policies and regulations. Many of these are related to race. Whether we notice or not, hair plays a substantial role in determining one’s place in a given society. Most of the works mentioned above are, I believe, responding to how whiteness orients perceptions and expectations, how it’s gaze is central and how it positions itself as the norm.

Hair is as relevant as skin color when it comes to racial discrimination. A 2014 New York Times article, for instance, makes a case for military regulation in the United States to be reconsidered as it did not take black service women into account when describing acceptable hair styles for military personal. US military revised its regulations on cornrows and dreadlocks in 2017, which was previously banned.

Similarly, in Apartheid South Africa, “pencil test” was used to determine whether one’s hair had “afro texture” to it, aiming to separate whites from the rest. It is clear that skin color was not always considered a good enough indication of whiteness. The tendency to discriminate based on hair did not end with Apartheid in South Africa. In 2016, Pretoria High School became the focus of attention, not just in South Africa but elsewhere too, as a teacher told a black student that her “afro was distracting other students”.

It seems black hair is often found “distracting” in various settings, not just in schools. One of the most prominent cases regarding policing black hair took place in 1999 when Venus Williams was facing Linda Davenport in Quarter Finals of the Australian Open. As beads from her hair flew to the court during the match, umpire penalised Williams for causing distraction. It is harder to imagine a situation where hair clip breaking free from a white player’s hair causing such penalty. Davenport later commented on the issue saying that it was not a total distraction “but it is a little annoying. It’s a little dangerous for her. I mean, she could maybe step on them”, making it about Williams’s safety, i.e. policing her hair for her own good.

Examples are endless, not all involving household names. In 2018, a young black wrestler in New Jersey was told to cut his dreads by the referee just before the game or “forfeit the competitions”.

BBC News Article

In 2017, a 12 year old pupil in the UK was sent home because his dreadlocks –worn tied up- was against the school uniform policy. In 2016, 14 year old Ruby Williams was also sent home repeatedly, using the same reason.

These are only a few recent examples, but the justification behind these decisions go back to an understanding that was created and shaped hundreds of years ago. For example, slaveholders in British and mainland colonies seemed to have allowed slaves “to style their hair as they please” although shaving the head was also used a as punishment (White and White, 49). Blacks were “not supposed to be proud of their hair” and any suggestion that they were would have sharply challenged complacent white cultural assumption” (White and White, 58). Black hair was seen as dirty, unkempt, woolly, a discourse that is part of an effort to maintain the assumed superiority of the white hair and therefore white race.

Probably one of the most important attempts to give legitimacy to structural racism, and to justify structural injustices it imposes and normalises, was eugenics and the scientists engaged in formulating the ideas behind it. In 1907, one such “scientist” engaged in coming up with scientific explanations for white superiority was the German scientist Eugen Fischer. Fischer designed a device to determine racial purity based on hair.

The device Haarfarbentafel[4] “was used not only to pin down racial differences but also to gauge levels of racial purity and impurity. Fischer took it with him to German South-West Africa (now Nambia), where he studied patterns of hereditary amongst people of mixed race. According to Fischer, Caucasians being the higher race, it is a degenerative act ‘for the highest races to mix with the lowest […], a pollutant that threatened the health of higher race.’ Once back in Germany he went on to establish the Society for Racial Hygiene in Freiburg and played a major role in promoting the sterilisation of mixed race children of African and German heritage in the Rhineland” (Tarlo, 167). The device was used in Nazi Germany to determine Jewish ancestry, in effect, writes Tarlo, becoming “one of a number of scientific instruments of death” (168).

How hair looks and the assumed common sense about what is tidy and presentable goes directly back to colonial ideas, to the attempts of fetishising and dehumanising those that were perceived as “exotic”. This did not end with slavery. Early 20th century visual culture in Europe was dominated by “freak shows” and “human zoos” that exhibited people from different parts of the world who looked “strange” to white Europeans. Their hair, eyes, buttocks, was perceived to provide fascinations for the Europeans, who bought tickets for these shows, to see mostly kidnaped people. The disappearance of “human zoos” coincides with cinema becoming a popular form of entertainment and neither the perception nor fetishising ended with freak shows. Oversexualised, dehuminanised display of Native Alaskans, East Asians and Africans never really left our visual culture. One of the first documentaries Nanook of the North (Robert Flaherty, 1922) is often read as a continuation of the early 20th Century spectacle human zoos.[5] It is therefore not surprising that during a TED talk Mena Fombo mentions how often strangers ask if they can touch her hair, and poses the question “how different this is from those who paid to go see Sarah Bartman?”

Such visual discourse that is interested in creating stereotypes, exotic, primitive images of the other, has a long tradition in photography too. Tamar Garb writes that “The camera was introduced to Africa soon after it was invented [and] a demand for typological images of ‘natives’ emerged in Europe, producing a lexicon of ‘exotic’ and ‘primitive’ prototypes and pseudoscientific ‘specimens’ […] Hierarchical notions of race joined modern technological inventions” (14). Garb writes this for a book produced in relation to an exhibition on South African photographers, and links the style of one of the most interesting contemporary photographers, Zanele Muholi, to colonial photographic practices. According to Garb, Muholi “manipulates traditional cultural signifiers to unleash them from the circuits of meaning in which they habitually reside” (60).

Photo Credit: Ozlem Koksal, Venice Bianele, 2019

As these examples illustrate, it is hardly surprising that issues related to hair are explored, either directly by utilising hair in the works themselves or by other means, in art and culture. Because it signifies and connotes so many different things (some interrelated some not), its use in art is similarly diverse, not always signifying the same thing or pointing at the same problem. However, they all point to its socialising aspect that goes beyond style or beauty, and often end up raising issues related to questions of power.

[1] Lorde, Audre. “Is Your Hair Still Political” in I am Your Sister ed. Rudolph P. Byrd et al. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009

[2] Turkey has changed its regulation on this matter within the last decade or so.

[3] Mutua M, Eddah. “Hair Is Not Just Hot Air: Narratives about Politics of Hair in Kenya” in Text and Performance Quarterly, 34:4 (392-394), 2014

[4] This, according to Tarlo, was often used together with two other devices, Augenfarbentafel (eye gauge) and Hautfarbentafel (skin gauge) (p 166).

[5] For an article on this topic see Fatimah Tobing Rony’s “Taxidermy and Romantic Ethnography” in The Thud Eye: Race, Cinema and Ethnographic Spectacle

References

Davis, Angela. Angela Davis: And Autobiography. London: Women’s Press, 1990.

Garb, Tamar. “Figures and Fictions: South African Photography in the Perfect Tense” in Figures and Fictions: Contemporary South African Photography Ed. T. Garb. London: V&A Publishing, 2011.

Hall, Stuart. “Living with Difference: Stuart Hall in Conversation with Bill Schwarz” in Soundings. Issue 34, Winter 2007.

Lorde, Audre. “Is your Hair Still Political” in I am Your Sister ed. Rudolph P. Byrd et al. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009

Mutua M, Eddah. “Hair Is Not Just Hot Air: Narratives about Politics of Hair in Kenya” in Text and Performance Quarterly, 34:4 (392-394), 2014

Mercer, Kobena. “Black Hair/Style Politics” in New Formations. No3, Winter 1997. Pp. 33-54.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. How to See the World London: Penguin Random House, 2015

Tarlo, Emma. Entanglement: The Secret Loves of Hair. London: Oneworld Publication, 2017.

Tobing Rony, Fatimah. “Taxidermy and Romantic Ethnography” in The Third Eye: Race, Cinema and Ethnographic Spectacle. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996.

White, Shane and White, Graham. “Slave Hair and African American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries” in The Journal of Southern History. Vol1, no 1 (Feb 1975) pp. 45-76.