9/10/2023

Writer and PhD researcher, Alice Mercier, reports on “In the Photographic Darkroom“, a conference organised by Dr Sara Dominici, scholar of photographic history and visual culture. Instead of viewing the darkroom as a neutral container for photographic production, this conference studied the darkroom as a space with its own materiality, rhythm and choreography.

In June 2023, the Institute for Modern and Contemporary Culture (IMCC) and CREAM at the University of Westminster hosted a two-day event for a critical discussion of the photographic darkroom. This conference brought together artists, writers, theorists, researchers, and scholars to contemplate the photographic darkroom as a somewhat overlooked space in the histories and theories of photographic image-making.

While the darkroom can perhaps be imagined or theorised as a singular space, the research presented at the conference illustrated not only the multiplicity of physical spaces that have operated as darkrooms (from laboratories, to kitchens, to tents), but also the evasiveness inherent in studying a space that is defined, in part, through its exclusion of light. Nevertheless, the speakers demonstrated how darkrooms are embedded within a tangible material environment (chemical, physical, architectural, visual), and how they can be understood as ambivalent spaces of production, labour, exploitation, protest, experimentation, study, community, and/or isolation. Darkroom spaces were shown not only to respond to – or interact with – the wider social and political environments within which they exist, but also, at times, to counter, and, at other times, to reproduce, the social and political atmosphere beyond the darkroom. The relationship between bodies and darkrooms was centred throughout; in the diaries and letters of colonial photographers; in nineteenth-century accounts of darkroom poisonings; through reports of working conditions for technicians in industrialised film processing labs; in the study of darkroom printing in opposition to regimes; and through the broader consideration of darkrooms as spaces wherein the hierarchies and power dynamics of a time and place might be either eschewed or re-inscribed.

Sara Dominici (University of Westminster) opened the conference with an introduction to the idea of the darkroom as a space of photographic knowledge, noting the many configurations of darkroom spaces that are connoted with the term “darkroom”, as well as the physical and elemental interconnectivity of darkrooms with their wider environments. The darkroom, as such, was posited not as a sealed-off space, but rather as physically and conceptually enmeshed. Dominici concluded with two questions that would underpin the discourse over the two days: can the darkroom be recognised and theorised as an entity in itself; and how might a theory of darkrooms alter existing theories of photography?

Day One: Establishing the Darkroom Atmosphere

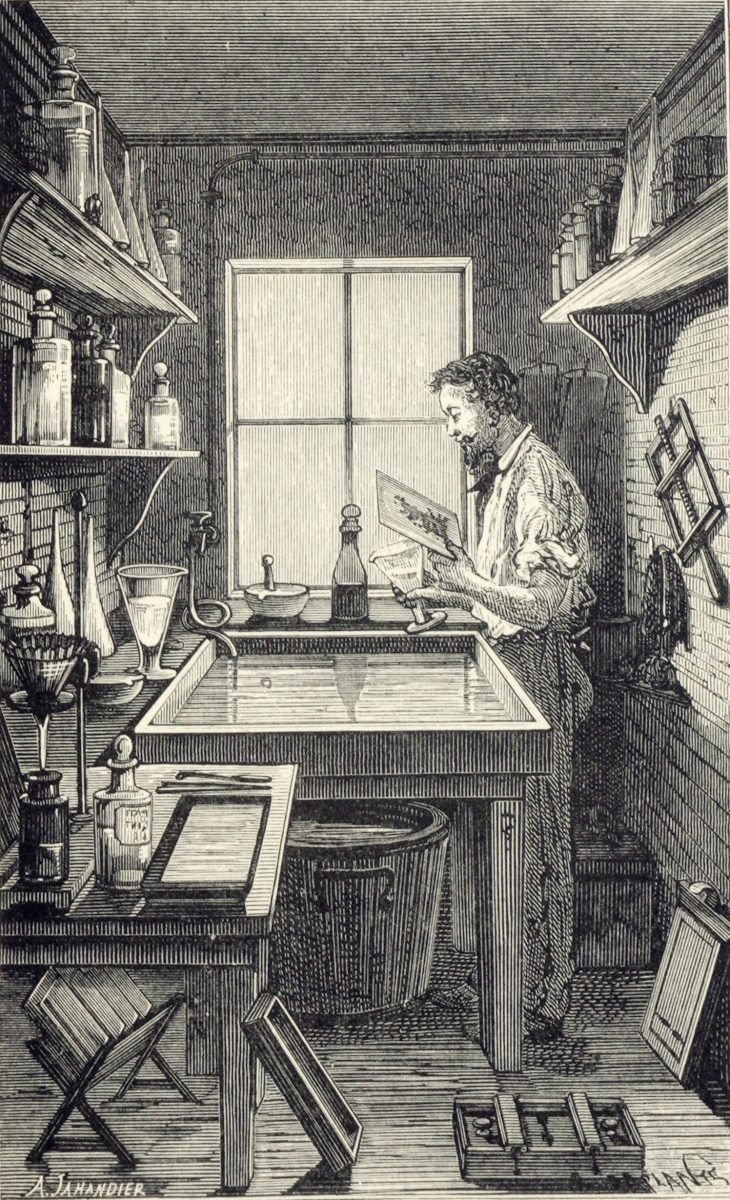

Establishing the groundwork for how the darkroom might be theorised as an entity in and of itself, several speakers addressed the spaces that constituted darkrooms, including the frequency with which the nineteenth-century darkroom asserted itself as a potentially dangerous place. Jennifer Tucker’s (Wesleyan University) keynote lecture detailed the risk of poisoning and illness frequently associated with chemicals routinely used in darkrooms (particularly potassium cyanide). Tucker’s research drew attention to a recurring topic of discussion between nineteenth-century photographers about the body and the darkroom, and about chemical photography’s detrimental effects on photographers’ health. The darkroom as a perilous space of concealed chemical hazard was particularly haunting, Tucker noted, given that symptoms of poisoning might only occur after it was too late to prevent injury or death. The notion of the nineteenth-century darkroom as an ominous or risky space could also be seen to indicate the role of darkrooms in the cultural imagination of twentieth-century film, TV, and literature, in which, as Tucker illustrated, darkrooms have been used to visualise “life lessons”, as spaces of transformation and disclosure.

The following panel considered the darkroom in terms of sensory experience and identity. Rowan Lear (University of Cumbria) detailed the darkroom as a space of “sensorial excess”, which corresponded with a heightened attention to one’s body, movements, and identity. Lear’s paper illustrated the darkroom as a space demanding stabilisation, and as an environment determined, to some extent, by considerations such as the optimal temperature for chemical processing. The theme of heat threaded through Lear’s paper, both in reference to the absence of embodied experiences in allegories for photography (i.e., in Plato’s cave), and as a contributing factor to the 1976-78 trade union industrial dispute at the Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories. The working conditions at Grunwick were also central to research presented by Kirsty Sinclair Dootson (UCL), which considered the conventions of the family snapshot, and the often-unseen labour of photo lab technicians amid increasing demands for fast photo processing following the availability of affordable film cameras. Both Lear’s and Dootson’s research considered race, gender and class in relation to the darkroom, and the Grunwick film processing lab, where the workforce was predominantly women, and reflected commonwealth migration to the U.K. following the breakdown of colonial rule. In Dootson’s research, the industrial action at Grunwick can be seen to foreground how both (post-)imperial Britain and the industry of photography sought to appeal to a white middle class – as the image of “Britishness” – at the exclusion of, and with disregard for, the workers processing photographic film. In this way, the strike at Grunwick made visible the exploitation of industrialised image making in Britain.

How far conventions in photography are shaped by institutions and technologies resonated throughout the research presented, and was directly addressed in Beatriz Pichel‘s (De Montfort University) paper on medical darkrooms. Pichel highlighted how, at the turn of the twentieth century, hospitals received funding for photographic equipment and facilities (e.g., the darkrooms at the Salpêtrière). These darkrooms were often situated within hospital laboratories, and, as Pichel highlighted, were therefore at the heart of scientific and medical research. Medical darkrooms required specialist skills from technicians, who would work with photographers and doctors to ensure that photographs documented medical conditions as they were intended to appear. Pichel’s paper illuminated how medical darkrooms can be seen to have had a significant influence not only on the conventions of medical photography, but also in establishing medical photography as a distinct branch of photographic practice and knowledge.

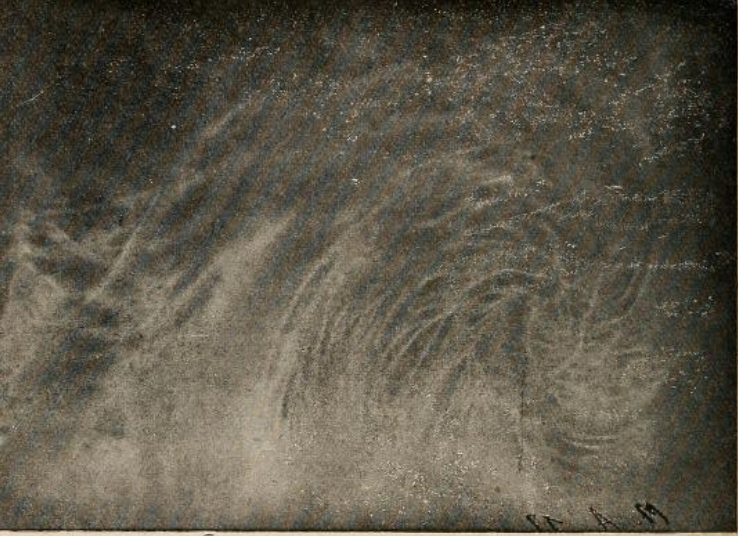

Staying with the influence of medicine on photographic imagery, Junko Theresa Mikuriya (University of West London) discussed the photographic practices that underpinned Hippolyte Baraduc’s theory of medicine and the soul, illustrated in his book, The Human Soul. Mikuriya detailed how Baraduc’s darkroom “iconography” was presented as distinct from photography because the images were said to be formed through human and cosmic vibrations, rather than light (and were therefore posited as evidence of the human soul). In a time of spiritualism, animism, magnetism, and spirit photography, Baraduc’s theory of the soul drew on existing theology and cosmologies, and, Mikuriya noted, his findings could be seen to reflect a “compulsive drive to see resemblances and equivalence everywhere”. Through Mikuriya’s research, Baraduc’s theories and evidential use of photography can be understood to interlock within a self-fulfilling system of signs, in which patterns, shapes and repetitions were interpreted as “proof”, through a framework that Baraduc himself had defined.

The extent to which photography’s role in the occult overlapped with its reputation for trickery or fraudulence was addressed by Efram Sera-Shriar (University of Copenhagen), whose research traced a series of challenges and responses to the credibility of William Hope, a spirit photographer practicing in the early twentieth century. Sera-Shriar’s paper followed the story of the magician-turned-debunker of spirit photography (William Marriott) who challenged the legitimacy of the trusted spirit photographer (William Hope) through a series of experiments and tests, including a seance attended by the then-editor of the Sunday Express, James Douglas. Although Hope was not found to be tampering with the images during the challenge, the space of the darkroom was figured as a probable site for any sleight of hand or swapping of plates. Through the papers presented by Pichel, Mikuriya, and Sera-Shriar, it’s therefore possible to read the darkroom as a space of heightened reception, with the potential of exposing something otherwise unknowable to the senses (whether in the realm of science and technology or spiritualism) and, by extension, as simultaneously a site of potential fraud or manipulation.

Chaired by David Cunningham (University of Westminster), the next panel addressed the practical and political concerns of photographic processing and innovation. Jo Gane‘s (Birmingham City University/De Montfort University) paper considered John Percy’s metallurgical laboratory, with its shaded areas for working with light-sensitive materials, as analogous to the darkroom. Gane’s research further investigated the crossover in materials and technologies used in electro-plating and photography (as well as in other industries) through the records that exist, in part, because of overlaps in (or infringements upon) the patents of scientists, inventors and practitioners working in either field during the nineteenth century.

How darkrooms adopt or promote a culture of image-making that is distinct from the dominant culture of wider society was addressed in both the presentations that followed. Núria F. Rius’s (Pompeu Fabra University) research centred on workers’ athenaeums in Barcelona in the early twentieth century, where darkrooms cultivated a photographic culture among workers which ran counter to bourgeois image culture, noting that athenaeum members would’ve represented a range of beliefs and political affiliations, and members utilised the darkrooms to make images that more faithfully reflected themselves and their points of view.

Uschi Klein’s (University of Brighton) research on the use of DIY darkrooms in communist-era Romania (specifically during Nicolae Ceaușescu’s “Golden Age”) underscored the risk to photographers who made images that did not endorse the communist regime. In this sense, darkrooms could be seen as spaces of resistance and opposition, as well as of risk or fear. Klein’s research drew from first-hand accounts of photographers, and described the threat of imprisonment to street photographers if, for example, taking photographs of queues outside food stores, as this would’ve been seen to undermine the regime. That photographs had to be both taken and processed covertly also arguably shaped the images made, and might, for example, determine anything from the framing and angle of a photograph, to the storage and distribution of darkroom chemicals, films, prints and equipment.

The final panel of the first day considered contemporary darkroom practices within their social, economic, environmental and creative contexts, with Carô Gervay, David Whiting, and Jonathan Blower from The Gate Darkroom describing how a community darkroom can function both as a collective art space, and a non-profit enterprise that is not reliant on arts funding. Following this, artist Justine Varga reflected on the experience of moving through the complete darkness of the colour darkroom, and the necessary rehearsal and repetition of movement that builds both the sequence (or choreography) of work, and familiarity with the darkroom space. The proceeding discussion turned to the experience of time in the darkroom, and the degrees of agency that are lost or gained with analogue practices. The experiential shifts that come with photographic technologies were expanded upon in the second day of the conference, through Catherine Troiano’s (V&A) paper, which explicated how the study of analogue darkrooms might strengthen understandings of present-day photographic practices; in Britt Salvesen’s (LACMA) presentation, which paralleled Jerry Uelsmann’s multiple-negative printing, with Adobe’s photoshop testing, illustrating the overlap between experimental darkroom processes and the functionality of digital image software; and in Anja Hysvær Langgåt’s (Norwegian Museum of Cultural History) study of Leif Preus’ Colour Art Photo and the photo finishing industry in Norway amidst a major shift in processing and photo-finishing practices in the twentieth century.

Day Two: Situating the Darkroom Environment

The second keynote lecture of the conference was delivered by Michelle Henning (University of Liverpool) and attended to the environmental impacts of industrial darkrooms, with reference to Ilford in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century. Henning’s paper traced the progression of Ilford’s darkroom spaces, and, more broadly, of the industry’s move away from the city centre as manufacturers strove for increasingly purified spaces – free from the London smog – in which to develop and dry photographic plates. Henning’s research highlighted that chemical photography also depended on extraction and heavy industry for its raw materials. Industrialised photography, as a chemical industry itself, had already contributed to irreversible damage to the land and atmosphere, and the industry’s proceeding attempts at air purification within the factory only further compounded this. In other words, the factory’s perceived “purified interior” was inseparable from the industry’s degradation of the external environment.

How darkrooms demarcate or intimate an interior space distinct from the wider environment was further explored in the research presented by Sean Willcock (University of Oxford), Elizabeth Watkins (University of Leeds), and Chris Balaschak (Flagler College, St. Augustine, FL). Willcock’s paper considered the writings of nineteenth-century photographer John Thomson, and the idea of the darkroom tent as a space of colonial anxiety, noting that portable darkrooms were spaces in which colonial photographers, such as Thomson, attempted to establish and stabilise an interior space distinct from the heat and light outside that might evaporate chemicals or fog photographic plates. As such, Willcock’s paper situated colonial darkroom processing within a wider culture of colonial images, projections and fantasies. Watkins’ presentation also centred around darkrooms and processing practices on the move, with a focus on William Colbeck’s Antarctic expeditions, and how expedition photographs illustrate the overlapping social, cultural, medical and imperial interests in photography. Expedition photography also revealed the networks of people involved in both the expeditions, and the production of images, challenging the notion of the lone explorer (or photographer) in the imperial imagination.

Balaschak’s paper turned to the second half of the twentieth century and the Visual Studies Workshop (VSW) in Rochester, NY, as a kind of alternative practice space in and of itself; one that broke away from the establishments of industrialised photography (epitomised by Kodak, also based in Rochester), and from the toxic and unsustainable processes of silver-based photographic printing. Balaschak highlighted environmentally concerned photography from the VSW that departed from the conventions that had come to signify artworks as environmentally conscious. Instead of the “clean” aesthetic of environmental photography, the Visual Studies Workshop images could be seen as “polluted” through their reuse of negatives and the utilisation of cheap non-silver printing. The VSW images might therefore be seen to resist the idea that spaces of image-making can be kept separate from the environments they are made within.

The potential (im)permanence of darkroom spaces was addressed in Michael Pritchard’s (Royal Photographic Society) chronology. Pritchard highlighted how early chemical processes demanded spaces that were not only dark, but also sterilised, which presented a hurdle for amateur photographers. With the introduction of dry plates and pre-cut film, however, amateur photography expanded, and Pritchard’s paper traced the emergence of ad hoc darkrooms in kitchens, basements, bathrooms, and cupboards under the stairs; semi-permanent darkrooms in sheds and converted rooms; and portable darkrooms in the form of perambulators, umbrellas, changing bags, and developing tents.

By the early twentieth century, camera and film manufacturers had begun depicting women in their advertisements, as research shared by Zsuzsanna Szegedy-Maszák (Indiana University/Hungarian National Museum) demonstrated. Szegedy-Maszák’s presentation considered adverts that appealed to women amateurs by emphasising, for example, that, with Kodak, there was no need to enter a darkroom. An advert suggesting that women chose not to enter darkrooms, however, might not reflect things as they were so much as an idea that fulfilled the commercial interests of a manufacturer, as Szegedy-Maszák highlighted in discussion on the extent to which adverts illustrate the past. Szegedy-Maszák’s paper thus considered adverts not so much as recording habits, beliefs, trends, or practices, but instead “sow[ing] the seeds for a future one” that would serve the interest of a brand.

The closing panels contemplated both historic and digital darkrooms, as well as differing approaches to working with archival materials. Franziska Lampe’s (Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte) research studied the movability of nineteenth-century darkroom spaces for photographic reproductions of artworks, with reference to the use of pop-up studios outside national galleries, and the more permanent studios and darkrooms within publishing houses. Lampe’s paper referred to photographic spaces acquired by the Bruckmann publishing house in Munich, circa 1900, and to Hugo Bruckmann’s influence in visual – particularly photographic – culture in relation to his role as promoter and publicist for the Nazi party. Through Lampe’s research, it is therefore possible to see photography used both in the service of an apparent democratisation of art, while at the same time implicated in the promotion and propaganda of fascism.

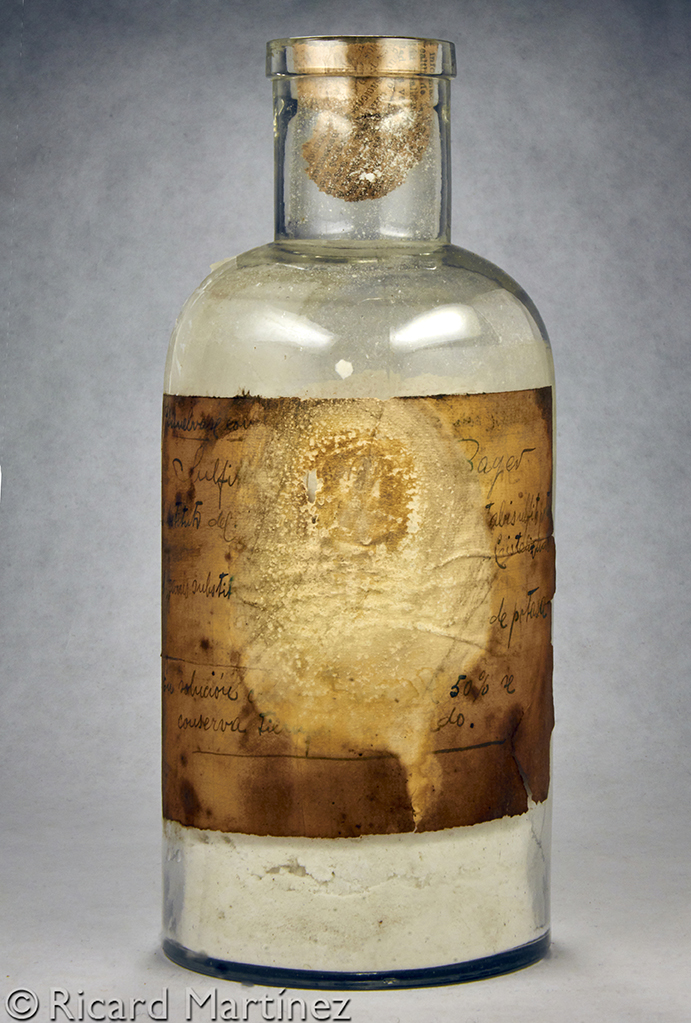

Offering a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach to historic materials and spaces, Ricard Martínez Teruel and Susanna Muriel Ortíz (Arqueologia del Punt de Vista) shared research and artwork that explored the objects and chemicals recovered from workspaces of photographer Jaume Ferrer Massanet (1872-1922). Teruel and Ortíz’s presentation contemplated the remains of the darkroom, the chemical traces of Massanet’s impetus to photograph, and the evidence of family life inscribed in Massanet’s darkroom materials. Teruel and Ortíz also discussed the duration of these found objects that connected different generations of artists together. As such, the processes of photographic image making in use today might be seen to be layered over those of Massanet’s time and place, and vice versa. This, in turn, called back to an idea introduced at the start of the conference, through Tucker’s work, and a theme that threaded through the event, about the darkroom as a space of both dormancy and disclosure.

To conclude the conference, Kelley Wilder (De Montfort University) chaired a plenary session with Sara Dominici, Michelle Henning, Lucy Soutter, and Jennifer Tucker, which reflected on the idea of the darkroom as a boundary object, inseparable from social histories and conceptualisations of inside and outside, while also defined, in part, through its porousness. As such, darkrooms emerged as enduringly relevant, not only in the making of photographs, but also as a tangible way to study and understand photographic processing practices in relation to the structures, environments, and networks they are embedded within.