Conversation at Pompidou Pavilion, Musée National de Céramique, Sèvres, Cité de la Céramique, Paris on 6 May 2016.

Participants: Alun Graves, Senior Curator, V&A Museum, London, UK; Glen R. Brown, Professor of Art History, Kansas State University, USA; Namita Gupta Wiggers, Independent writer, curator and educator, director of the Critical Craft Forum, USA; Christie Brown, Professor of Ceramics, University of Westminster, London, UK; Clare Twomey, Research Reader, University of Westminster, London, UK and Hyeyoung Cho, Independent Curator, adjunct professor, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea.

Facilitator: Kim Bagley, Research Associate, University of Westminster, London UK.

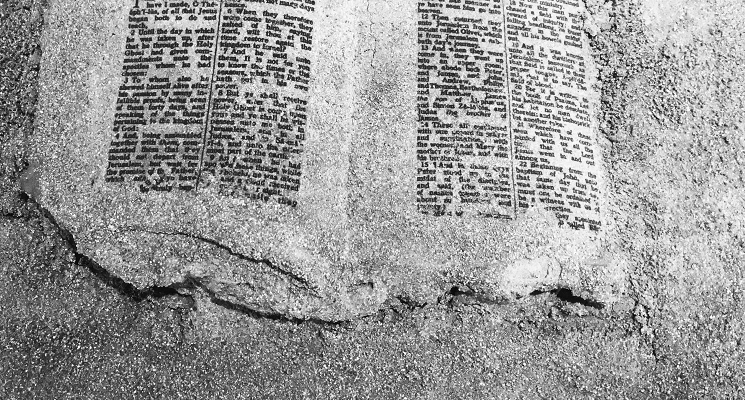

The question of what kind of documentation is appropriate for ephemeral, time-based works, or temporary exhibition installations is an important one for curators and artists working within an ‘expanded field’ of ceramics. One of the ways artists and curators tackle this question is to introduce another collaborative element to the existing relationship between artist and institution. Here, curators Hyeyoung Cho and Alun Graves have discussed examples of photography and videography that interpret as well as document. The documentation may become another element of the work that, like the collaboration between artist and institution, requires careful thought and involves elements of risk and trust.

Christie: Once the exhibition’s up and finished and perfect, were all those photographs available as a separate sort of exhibition?

Hyeyoung: The photographs were paying tribute to everyone who participated, as well as the photographer. After the exhibition we gave a copy to the people involved.

Christie: Oh I see, because you would be fascinated to see this beautiful, finished installation and then actually see images of the half made.

Hyeyoung: We are going to continue working because we found it was very effective for our next project. She’s also coming to Bernaudaud to document an exhibition in the summer. I see it as a way of introducing new people into the field.

Christie: I’m always aware of how the general public are fascinated by the process of making things, just as we are, which is why when Alun showed that picture of the steel ring in the factory, we all gasped; it’s just so interesting, what goes on behind the scenes.

Alun: It is, but then so much of what I love about Hyeyoung’s images is that there’s a delightful kind of artifice about them as well. It’s not just a raw process; they are beautifully composed images. Are they in the public domain? Were they put together as a catalogue?

Hyeyoung: Yes, it was a catalogue.

Namita: I think it’s the difference between documentation and interpretative documentation?

Alun: That’s an interesting term, I don’t know it …

Namita: I just made it up!

Alun: One of the things that really interests me at the moment about documentation, which everybody has talked about, is who’s responsible for it or where does the true documentation lie in these things that are ephemeral? Keith’s work, Moon – the exploding drum kit – is a great example. Sometimes the artist may commission their own documentation and control how that appears. On the other hand, the artist may wish to delegate it elsewhere. There are various films of Keith’s practice floating around. He has sometimes used a really wonderful filmmaker called Jared Schiller who’s made some very beautiful films. I think it’s very true testament to his work but for Moon the V&A did a film; I really don’t like it, it’s too clean, but there’s YouTube footage from members of the audience and to me, it’s a far more truthful record of what the event was about. So in terms of those longer-term questions about how one documents this kind of practice, then I think yes, who’s responsible for it?

Hyeyoung: It all goes back to collaboration. For my project, it was a collaboration as well. I just said, ‘Come and do this, you can do whatever you want’. And I’m happy because you have to respect the artist to do her work.

Alun: I think that’s what’s beautiful about Jared’s films of Keith. Keith will respect the views of the filmmaker, who then made a very beautiful film; it’s Jared’s film, but it’s also a form of documentation. And I think that’s a great way to go if you can find the right person to do that.