Monday 10/6/2024

In March 2024, CREAM supported the two-day conference, Women in Revolt: Radical Acts and Contemporary Resonances. Hosted by Tate Britain, the conference presented current debates on feminist art practice from an international array of speakers. Through a discursive programme of panels, artist talks, roundtable discussion and reading groups, the conference set out to situate the historical focus initiated by the Tate exhibition Women in revolt! Arts and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, as part of a wider contemporary and global context. The conference was organised by CREAM’s Dr Lucy Reynolds, together with Dr Claire M. Holdsworth (Central St Martins, UAL). CREAM PhD candidate and Techne Scholar, Lauren Houlton assisted in the research and production of the conference. Here, she reflects on its success and place within the history of radical feminist art practices.

One of the first artworks encountered on entering the exhibition, Women in Revolt! Arts and Activism in the UK 1970-1990 at Tate Britain, is Sue Crockford’s film, A Woman’s Place (1971). It documents the first Women’s Liberation conference held in Ruskin College, Oxford, in 1970; an event which is now credited as an important milestone in the history of the 1970s women’s liberation movement in Britain. In the exhibition it is presented as a catalysing moment, breaking the isolation experienced by many, when hundreds of women gathered across the country to voice aspects of their personal and social lives that were rarely spoken of in the public domain. Though the start of something is rarely its true beginning, it was fitting that a conference took place as part of the Women in Revolt public programme in the penultimate week of the exhibition, marking the end of the exhibition at Tate Britain with an event reminiscent of the moment that bolstered much of the activism underscoring the exhibited artworks. Gesturing to the significance of the historical event at Oxford twenty-four years prior, the conference titled Women in Revolt: contemporary acts, historical resonances, brought together feminist practitioners in a pedagogical space to share research, projects, and ideas on feminist live and moving image art practices.

In a spirit of refusing master narratives, there were no keynote lectures – a notable departure from the standard academic conference model. Instead, nine panels were staged across two days, comprising artists, art historians, curators, and archivists, ranging from early-career and established practitioners, alongside a programme of ‘break out’ workshops and reading groups. Papers were broad in scope, expanding on the British context of the exhibition to include feminist research and practices spanning different geographical and historical contexts, social locations, and various aesthetic strategies. Feminist artists have frequently been relegated to the margins, but in resisting the centring or prioritising of certain papers or panels over others, the conference enabled a plurality of perspectives to be held together, an arrangement that sought to mitigate the ways discursive structures have historically determined how certain ways of making, and ways of thinking, about feminist art have been valued over others.

Despite the breadth of the conference’s scope, the question; what is the value of returning to these artworks now?, pervaded across the two days. This was addressed in the first panel, Other ecologies: collective work and the politics of space, when its panellists located their research on feminist artistic collectives in the various social, cultural, and political contexts informing their work. Lina Džuverović (Chelsea College of Art, University of the Arts London) discussed her research into 1970s Yugoslavian art collectives in relation to the current institutional enthusiasm for collaborative and collective models of artmaking. Isobel Harbison (Goldsmiths, University of London) positioned her research into the Derry Film and Video Workshop (DFVW), a women-led film production company founded in 1984, in the aftereffects of Britain’s referendum result to leave the European Union; whereas two feminist film curatorial collectives, Invisible Women and TAPE Collective, discussed how their more recent programmes focusing on communality and contact were motivated by their desire to bring people together after the isolation of Covid-19 restrictions. The mapping of these different contexts emphasised the ground on which research takes place and how these inevitably inform the historical material that researchers turn to. This first panel also prompted a hum of recognition from those in the audience when Džuverović, in her presentation, gave a concrete example of a power differential arising through her interactions with a male and female member of a mixed gender art collective. Recalling an interview that she had arranged with a women artist of an art collective that she was researching, Džuverović described how the husband (who was also a member of the collective) took it upon himself to join uninvited and proceed to answer most of her questions. Meanwhile, the woman who Džuverović had wanted to speak to, excused herself intermittently to prepare lunch and attend to other domestic duties. Džuverović recalled this incident to contest the egalitarian ideals of unity, togetherness, and shared labour that are often attributed to art collectives by showing how gendered roles and expectations infiltrate and configure the dynamics in these spaces. The audience’s spontaneous and collective reaction showed these dynamics as all too familiar.

Harbison’s presentation on the Derry Film and Video Workshop (DFVW) focused on their film Stop Searching examining the unregulated use of the practice on women prisoners. Her presentation was hugely affective, as Harbison mirrored the narrative strategies used in the film to describe, rather than visually depict, the violence of strip searching when used by prison officers as a form of gender and sexual related violence, used to assault and humiliate women. The films of DFVW examine the issues raised in the women’s liberation movement as they intersected with the ‘national question’ of living under British rule, rooting women’s inequalities in the violence of the carceral state and state endorsed policies.

In the panel, Radical alchemy: alternative imaginaries and feminist encounter, the current neoliberal pressures being exerted on artists and researchers provided the lens through which various 1970s feminist art practices were discussed. Under increasingly precarious work conditions and requirements to make artistic production and research more efficient, the panellists reflected on the conditions of prior decades, namely access to the welfare state, social housing, and the legalisation of squatting, to consider alternative visions to the current and seemingly inescapable status quo. Amy Tobin’s (University of Cambridge) presentation explicitly cited the socio-economic conditions that meant women artists could live cheaply, affording them the freedom to live outside of the commitments of full-time waged labour. The ability to live in this way, Tobin suggested, shaped and frames the four-part performance Berlin (1976) by artist Rose English and filmmaker Sally Potter. Staged across various squatted locations that included the townhouse in Mornington Terrace in London that both artists shared, an ice rink in Swiss Cottage and a swimming pool in Islington, Berlin comprised various performances by English and Potter that drew from archetypes borrowed from cinema, ice skating, surface diving, and synchronised swimming, among others. As a co-authored performance that was also dependent on the contributions of numerous artistic peers, Tobin proposed that Berlin reflected alternative forms of sociality that were growing at the time when artists were trying to organise their lives and the way they related to others in ways that resisted the individualism of capitalist relations. Tobin didn’t have time to expand on the artwork’s current relevance, but the evocation of fantasy and spectacle alluded to a fantasy life for feminism rendering ways of imagining otherwise. The squatting movement also underscored presentations by Maria Elena Buzck and Rebecca Bins who surveyed the unarticulated networks that allowed transgressive, feminist punk cultures to flourish through the works of Alice Bag, Vivienne Dick, Gina Birch and Anne Bean.

Within the same panel, Jennifer White’s (University of Manchester) presentation also invoked ideas of fantasy, when she discussed the political commodities of dream and desire through her reading of the film Dream On (1991) by Amber Film and Video Collective. The collective, who formed in 1976, is known for their film and photographic work capturing working class cultures, notably in the Northeast of England. They have been widely discussed in research on Britain’s workshop movement, but as White argued, no critical research has, as of yet, been conducted on their work from a feminist perspective. Dream On follows four female protagonists whose confrontations with disordered eating, sexual abuse, and alcoholism, are weaved through poetry, fantasy, and humour, provided primarily through a fairy godmother who appears periodically to support the women through magic and mystical guidance. Though Amber is a mixed gender collective, Dream On was written and produced by its female members and a women’s writing group based on the estate where the film is staged. Through the figure of the fairy godmother, White considered the film’s treatment of feminism and social mobility in Britain, arguing that its use of fantasy provided a political space for women to project their desires and dreams outside the frame of gritty realism. Across this panel, the genre of fantasy granted unlimited freedom to dream.

Questions of value and return pervaded throughout the conversation between artist filmmaker Onyeka Igwe and former member of Sankofa Film and Video, Martina (Judah) A t t i l l e when they considered alternative ways of introducing new generations to past films by Black British women experimental filmmakers. This was discussed primarily through the creative approach taken by A t t i l l e in staging cross-generational encounters in the workshop Dreaming Rivers Found Footage 2021 held by not/nowhere, a London film cooperative, at the Paul Mellon Centre. During this workshop, A t t i l l e invited participants to physically mark a small section of one of the last remaining 16mm prints of Dreaming Rivers (1988), a film that she had written and directed. A deep sense of anxiety would likely be provoked in some at the thought of making irreversible changes to a 16mm film print. Rather than present the invitation as detrimental to its preservation for future audiences, Igwe and A t t i l l e instead framed it as an incredibly generous offer with one participant noted as saying that the experience collapsed hierarchies between maker and audience. Through this generosity, both speakers questioned standard models of access, using the workshop as a provocation to suggest how Black feminist politics might shape and expand future conditions of encounter with experimental films. How may acts of care, generosity, and solidarity impact on how we preserve and where we preserve films, so communities can continue to gather around these for decades to come? Both speakers were clear in not wanting to frame the work of Black British experimental filmmakers through the lens of visibility (or historical invisibility). The openness and care shown by A t t i l l e towards the workshop’s participants raised the subject of exclusion implicitly, showing the role that the practice of care can have in establishing unity and friendship against the hostility of systemic marginalisation. As Christina Sharpe writes in Ordinary Notes (2023): ‘I want acts and accounts of care as shared and distributed risk, as mass refusals of the unbearable life, as total rejections of the dead future… To practice care is to keep trying, to repeat oneself in the hope that each repetition might, in the words of Fern Ramoutar ‘expand our capacity for survival’.

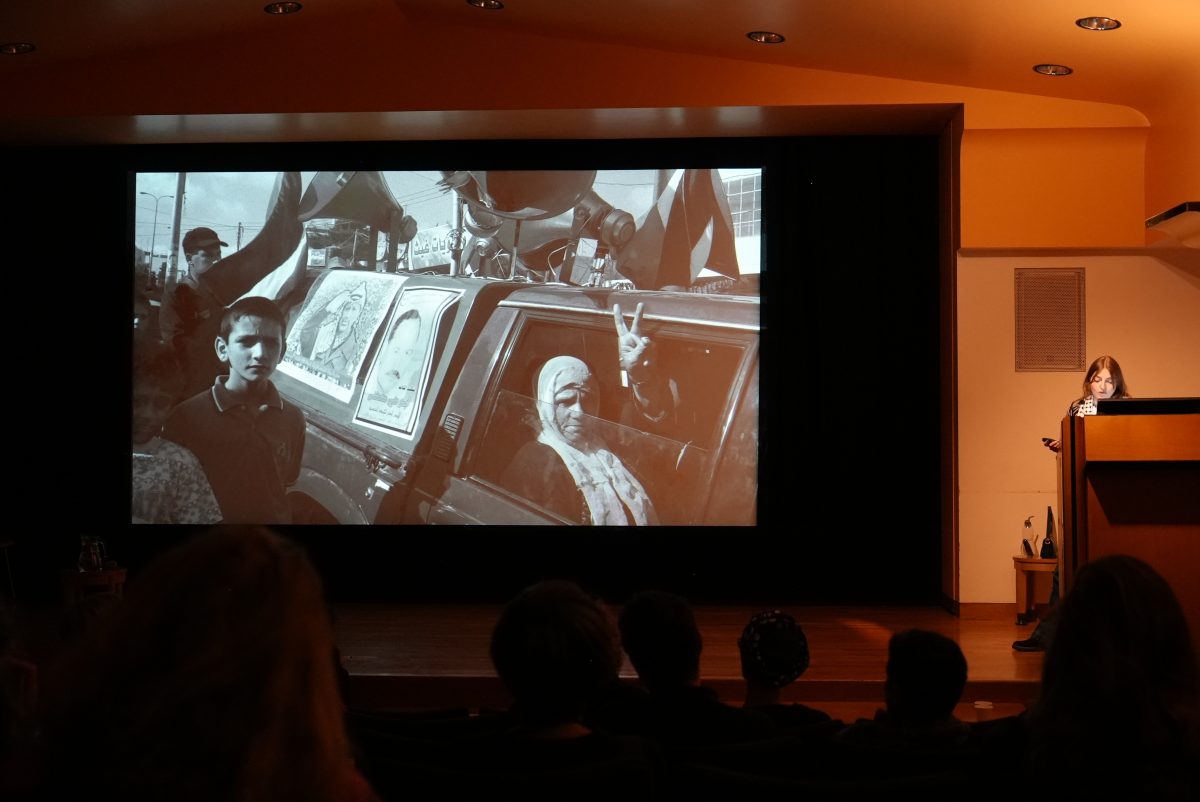

The current Israeli military action unfolding in Gaza (where over 30,000 people have died since 7 October 2023) made the focus on Palestinian women’s art in the third panel of the day, On Devaluation of ‘Women’s Work’: Female-led resistance and creative practice in Palestine in the 1970s-1990s and its legacy today, organised by CREAM PhD Researcher Nadia Yahlom, ever pressing. The first speaker, Zeinab Shaath – the daughter of a Palestinian Father from Gaza, described how she was able to maintain access to her Palestinian identity through Palestinian culture, including books, music, and dance, while growing up in Egypt. Here, culture functions as a form of preservation, a way of keeping Palestinian history alive in the face of systemic erasure. This stressed the significance of Israel’s attacks on cultural, educational, and archival infrastructures in Gaza which have included the destruction of Israa University, the last remaining university in Gaza, by Israeli armed forces in January 2024.1 That Tate had yet to publicly call for a ceasefire in Gaza was raised in the questions proceeding the panel, arguably revealing the institution’s own biases. The pressing question is how artists, curators, and researchers might productively respond to this.

The panel, Community-Building Filmmaking, examined the landscape of socially engaged feminist filmmaking in Latin America, past and present. Lorena Cervera Ferrer presented a rapid and short history of all-women Latin American film and video collectives working throughout the 1970s and into the 1990s. This illuminated an alternative lineage of feminist filmmaking outside the well-trodden euro-centric histories of North America and Europe. Livia Perez discussed the Brazilian videographers Norma Bahia Pontes and Rita Moreira who produced daring and innovative representations of lesbian love, sex, and motherhood, while living in New York in the early 1970s during the rising women’s liberation movement. Isabel Seguí (University of St Andrews) discussed the grassroots archive of Peruvian filmmaker María Barea, a focal agent in Latin American feminist, participatory filmmaking, by a collective comprising herself and other academics, archivists, and curators. Seguí highlighted meeting Barea entirely through chance encounter where she realised how prolific she had been as a filmmaker working both independently and as a member of numerous film groups including Chaski and WARMI Cine y Video. Commenting on how, on this occasion, the creation of her archive fell on the voluntary labour of feminist film historians, after Barea had been institutionally marginalised in Latin American filmmaking genealogies, Seguí framed the collective’s work as compiling counterhistories – ending with a quote from Barea that ‘our revenge is to be happy’.

In her introduction to The Past Before Us, socialist feminist historian Sheila Rowbotham describes borrowing the publication’s title from a quote: ‘the past is before us, the future’s behind us’. Recalling how it had stayed with her ever since first hearing it at a Hackney Young Socialists meeting many years prior, she applies it in her book to stress how the way one sees the past is intrinsically tied to the social, temporal, and geographical locations of the ‘I’ of the person who is looking. Though spanning two days only, the conference offered a snapshot of the extensive research and practice being undertaken in feminist moving image and performance. Presentations spanned from the rebelliousness to the humorous, the radically defiant to the aspirational. At times they were highly personal and thrillingly subversive, encompassing committed acts of care and generosity. Others were devastating to hear, as women recounted the painful realities of enduring patriarchy under global systems of social, political, and economic relations. But crucially, when seen together, the artists and artworks that were discussed resisted easily categorisation to a singular style or issue. Rather, the ‘I’ that was invoked throughout the conference was fundamentally plural, relaying women’s experiences in all their variability and specificity.

Lauren Houlton is a doctoral researcher based at the University of Westminster. Her thesis, Differentiated Publics: A Study of Feminist Collaboration in Artist’s Filmmaking, explores how feminism has informed the approaches of artists Petra Bauer, Andrea Luka Zimmerman, and Rehana Zaman, when working collaboratively in artist’s moving image.