Professor David Finkelstein reflects on his recent forays into the world of early 20th century picture postcards. Far from simply the picturesque views of local sights and famous buildings shared of our holidays, Finkelstein introduces how postcards reveal the movement of global print culture, from migrating personnel, print and press ideas to technology, imagery, and people.

What comes to mind when you think of the word ‘postcard’? Those of a certain age might think of holidays and excursions, of picture postcards circling lazily around small carousels outside tourist shops and visitor centres, waiting for you to pick out a card with picturesque views of local sights and famous buildings to send to a relative. You might scribble some quick note on the back: ‘wish you were here’; ‘enjoying myself tremendously’; ‘thinking of you (or not)’. It was a way of marking your presence in a physical space. You had visited, you had seen what was on offer, and this card was a record of that fact. Now, of course, the selfie taken on your mobile phone and posted instantly to social media, or sent as part of a text message, has taken over such functions: the image is caught, sent and seen within seconds.

There was a time when picture postcards were vital parts of a global cultural interaction. The world’s first postcards in the form we know them today (an image on the front, postal information on the back) were issued by the Austrian Post Office in October 1869. They were a resounding success, selling 2,926,102 cards across Austria-Hungary in the first three months of issue. The idea was picked up in Britain the following year. Other countries soon followed: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Holland, Norway and Sweden introduced postcards in 1871; France, Russia, Algeria and Chile in 1872; Spain, Japan and the U.S. in 1873. The implementation of an International Postal Treaty in 1875 and the Universal Postal Union in 1878, establishing consistent international postal charges and postal card sizes, galvanised demand for picture postcards, particularly when improvements in printing technology lowered costs of producing coloured and photographic images from the 1880s onwards.

Ephemera Collecting by Accident

I became interested in postcards by accident. For the past decade I have been working on creative industry labour migration, and the transnational movement of print personnel, skills, ideas and machinery across British colonial space and time. I am also curious about the way the creative print industry has advertised and represented itself to the outside world. I spend time uncovering and writing about printing trade journals and the creative work printers and compositors produced as part of a deliberate effort to shape and represent a specific trade culture identity for themselves as skilled artisans, particularly during the ‘long nineteenth century’. I have also written about so-called ‘tramping circuits’ that print unions developed from the 1840s onwards, which supported the movement of workers searching for work across local, regional and international trade networks.

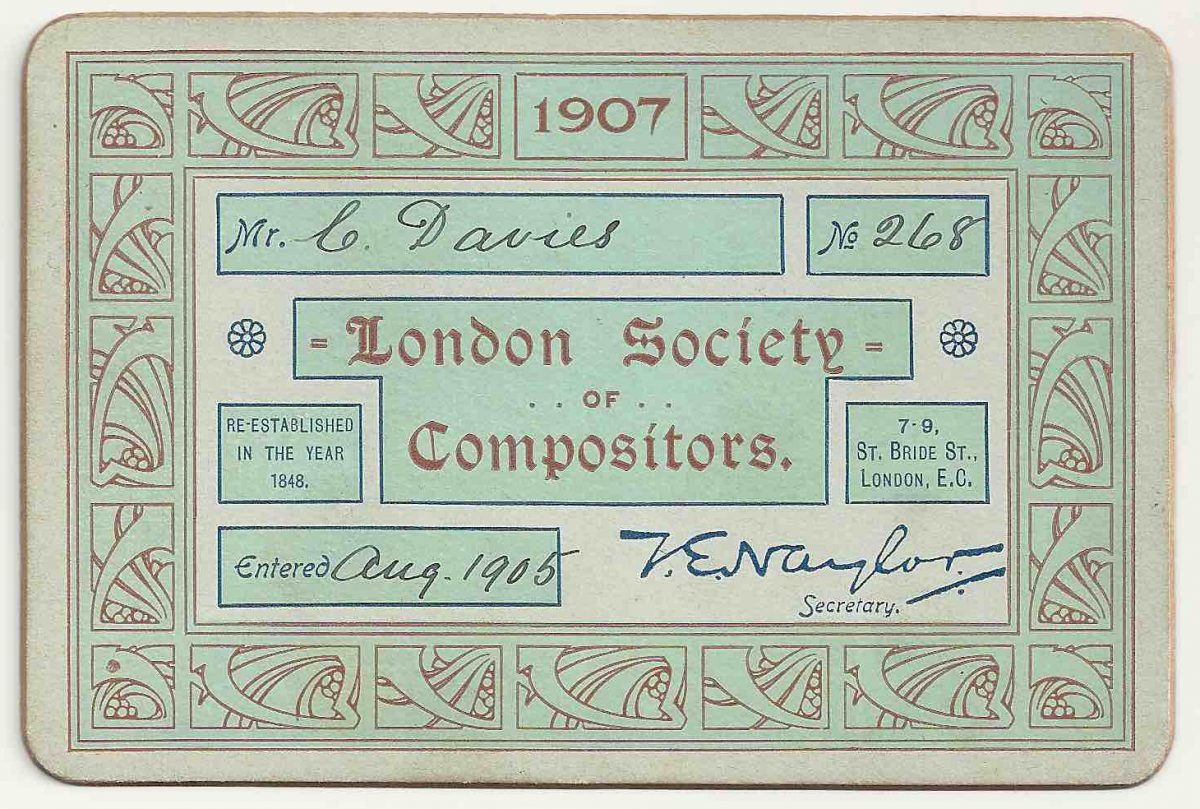

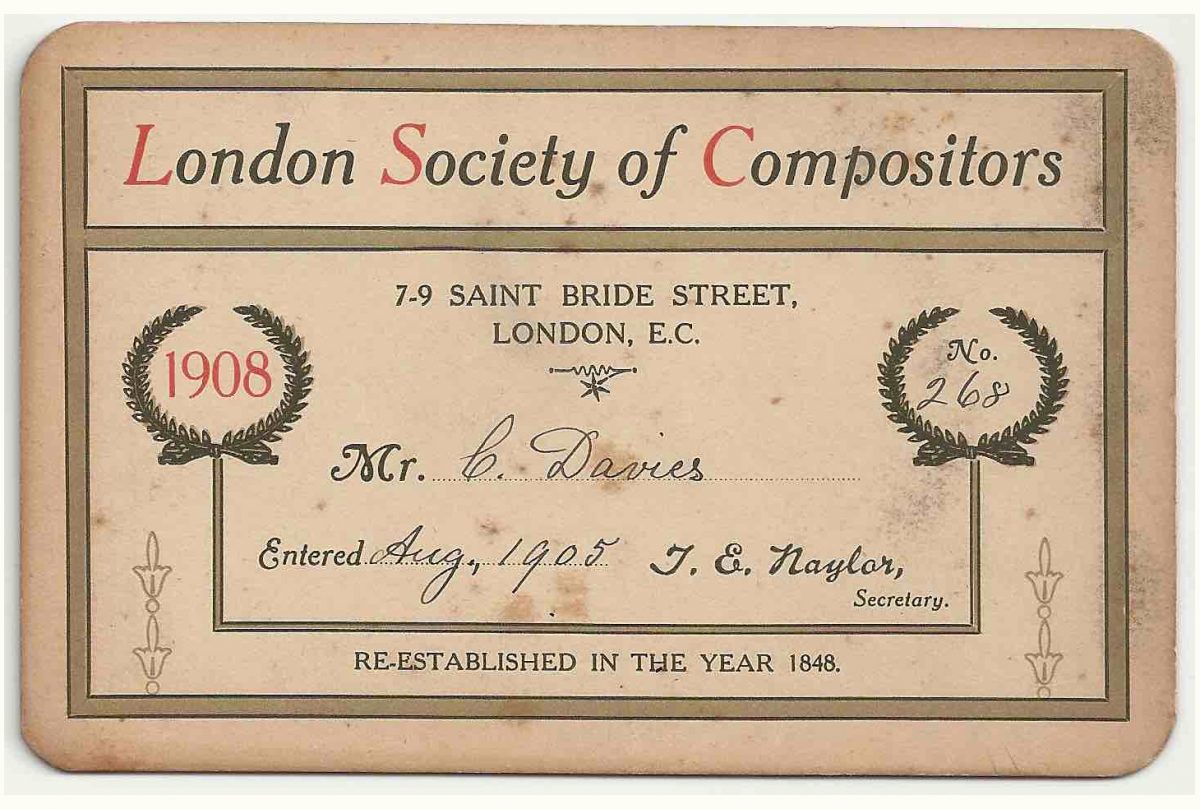

To provide documentary structure to such traveling circuits, unions issued membership and traveling cards that could be used to gain recognition of trade skills and entrance across affiliated branches. I began collecting related visual union ephemera, picking up along the way numerous examples of membership cards, trade posters and postcards with unusual visual designs. I found out about quirky competitions, such as the annual design scheme run by the London Society for Compositors between 1907-1953, where members were invited to submit card frontispiece designs, with the winning example featured on membership cards issued the following year.

I also began acquiring postcard representations of print industry workplaces and buildings. I was curious to know in what way the print industry represented itself in such visual forms, and for what purpose. I have picked up examples from the US, Canada, continental Europe, Australasia, Caribbean and East Asia, many produced between 1900 and 1950. Some were issued for advertising purposes; some were created to celebrate milestone moments in individual or company histories; some were produced as local postcard mementos; others stand as documentary representations of skilled artisans affixed to a specific time, place and task.

Japanese Picture Postcards and the Imperial Printing Bureau

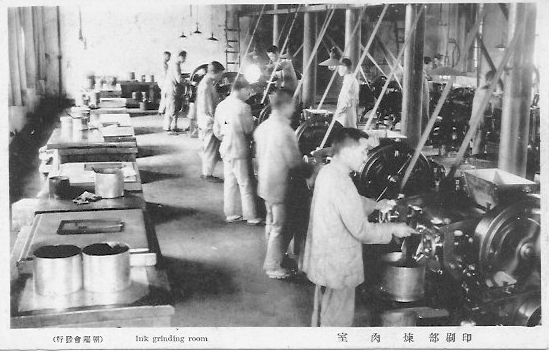

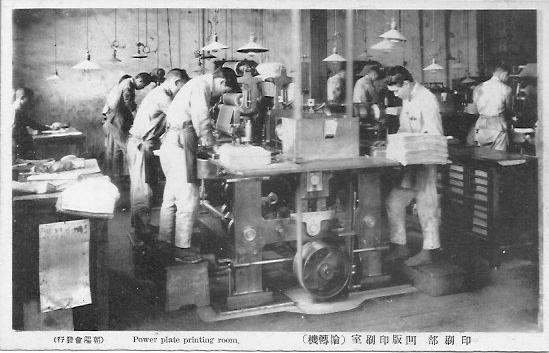

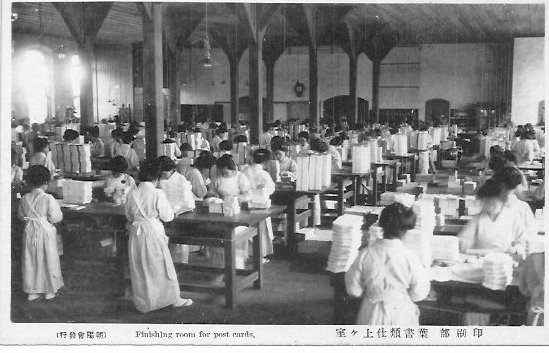

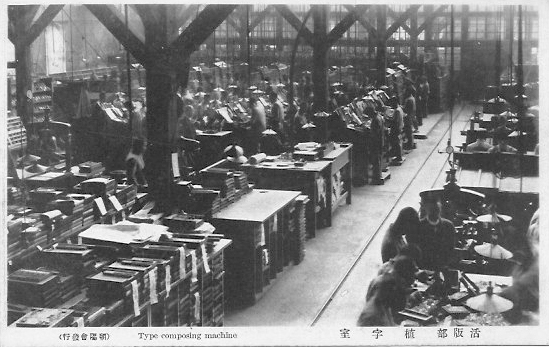

A postcard set I acquired by chance while on a speaking engagement in Japan in 2018 was an unusual collection of black and white postcards issued in 1921 by the Imperial Printing Bureau, based in Tokyo. The collection features a mixture of people, places and objects, documenting an early twentieth-century Japanese industrial print workplace in ways not addressed by contemporary studies of the picture postcard phenomenon.

Japanese postcard history commentary is sparse, though some insights have appeared sporadically over the last 80 years in English and Japanese language outlets, such as by Sekko Hibata, Ryûkichi Komori, Neil Pedlar and Kenji Satô. Japanese picture post cards became fashionable in the late 1870s with the reform of the national and international postal systems. The Japanese post office issued its first postcards in 1873. According to Fraser, between 1890 and 1913, picture postcard sales and mailings soared, with postings increasing from 96,430,610 cards in 1890 to 1,504,860,312 in 1913.ii Several private Japanese enterprises became extremely successful as a result, including Ogawa and the Akasawa Fine Art Co. in Yokohama, and Yamakashoten in Tokyo.

The Imperial Printing Bureau postcards, part of this postal bonanza, present something of a conundrum. Why depict such industrial print trade spaces? To whom were these cards directed? Who were they produced by and for what purpose? Why would the Bureau go to such lengths to document its shop floors, workstations and workers? Solving the mystery of their provenance took me down a rabbit hole of interests relating to a sub-genre of postcard history not previously considered, exposing the intersection between representations of place, space and industry. Studying these promotional images also raises the question of what role such visual ephemera played in representing and promoting the industrial workplace of the twentieth century modernist era.

Imperial Printing Bureau History

The Imperial Printing Bureau was founded in Tokyo in 1871. Its function initially was to bring order and consistency to the issuing of Japanese government banknotes. Previous attempts at printing Japanese paper money had been halting, shoddy and prone to counterfeiting. The Meiji government responded by bringing in external consultants and hiring foreign talent to help build and organise its printing spaces, press technology and workflows. Among these were Edoardo Chiossone (1833-1898), a Genoese bred art professor and engraver, who while working in the Frankfurt office of the graphic industry leaders Dondorf and Naumann in 1870, had designed and engraved the famous Japanese bank note that would come to be known as the ‘German made banknote’, (Doitsu sei no osatsu), put into circulation in 1873. On the strength of this commission, Chiossone took up an invitation to advise the Japanese government on latest printing and engraving techniques, and in 1875 settled in Tokyo to set up and manage the engraving division of the Imperial Printing Bureau as a foreign government adviser (Oyatoi Gaikokujin). Chiossone would spend the next 23 years in Japan designing and overseeing the engraving of over 500 plates for banknotes, stamps, government bonds and other securities issued by the modern Japanese state, as well as supporting print work on government publications. He would also gain renown as a portraitist of Emperor Meiji, producing a sketched portrait that would go on to be photographed and distributed in official documents, as postcards and as official images hung in schools, government offices and public spaces [see Figure 06].

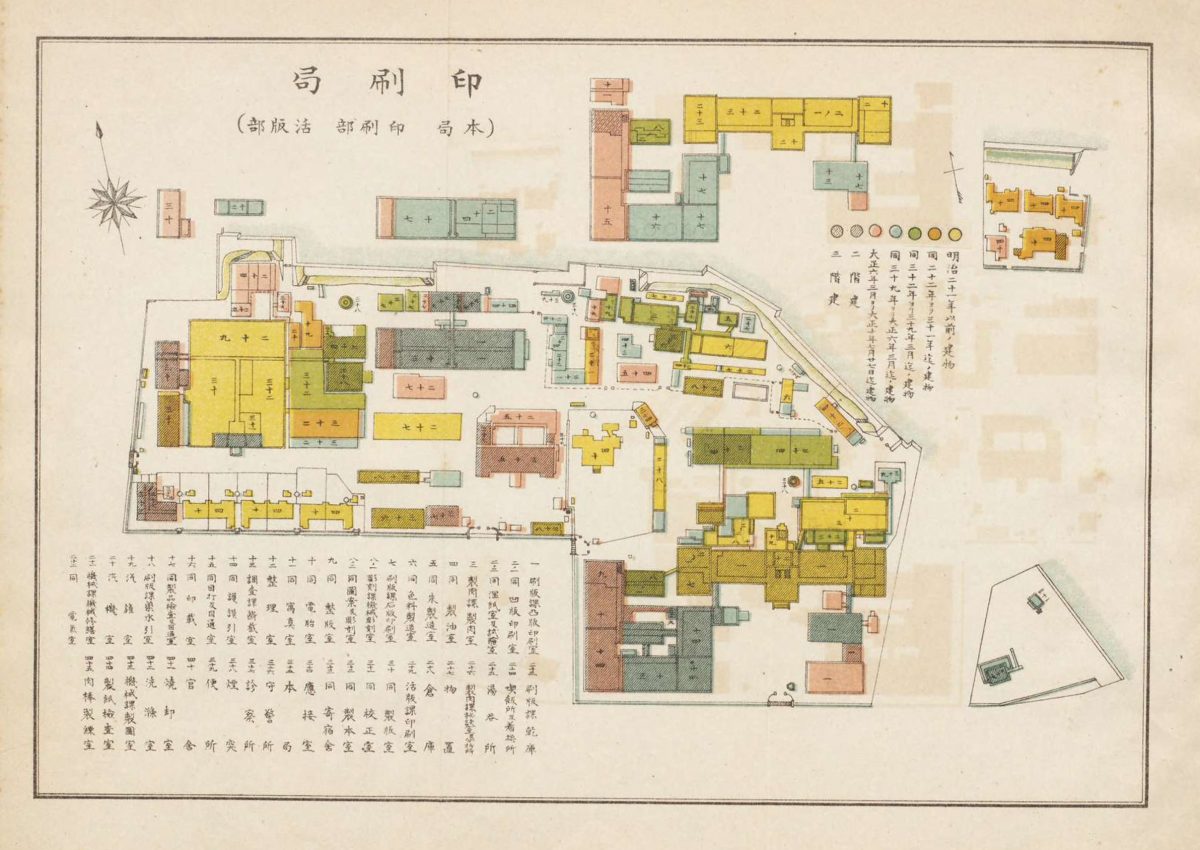

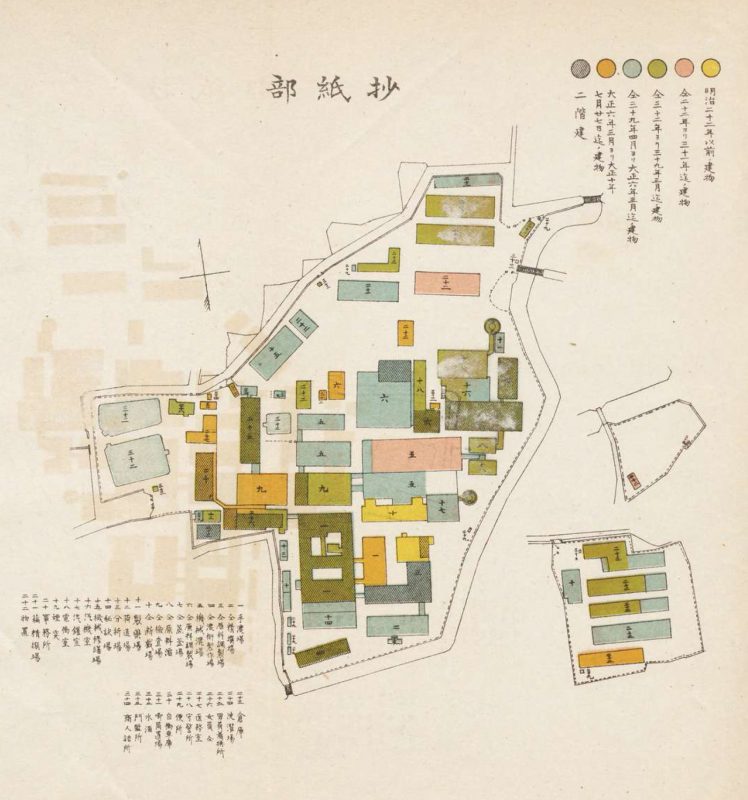

The Bureau started off with a focus on printing banknotes, but by the turn of the century it had expanded its remit to include printing official papers and documents produced for the Tokyo-based government. It was set up to be self-contained, with separate rooms dedicated to processing and producing the paper, ink and print needed, office space for engravers, draughtsmen and compositors to produce images and text required, and machinery to complete production of commissioned work.

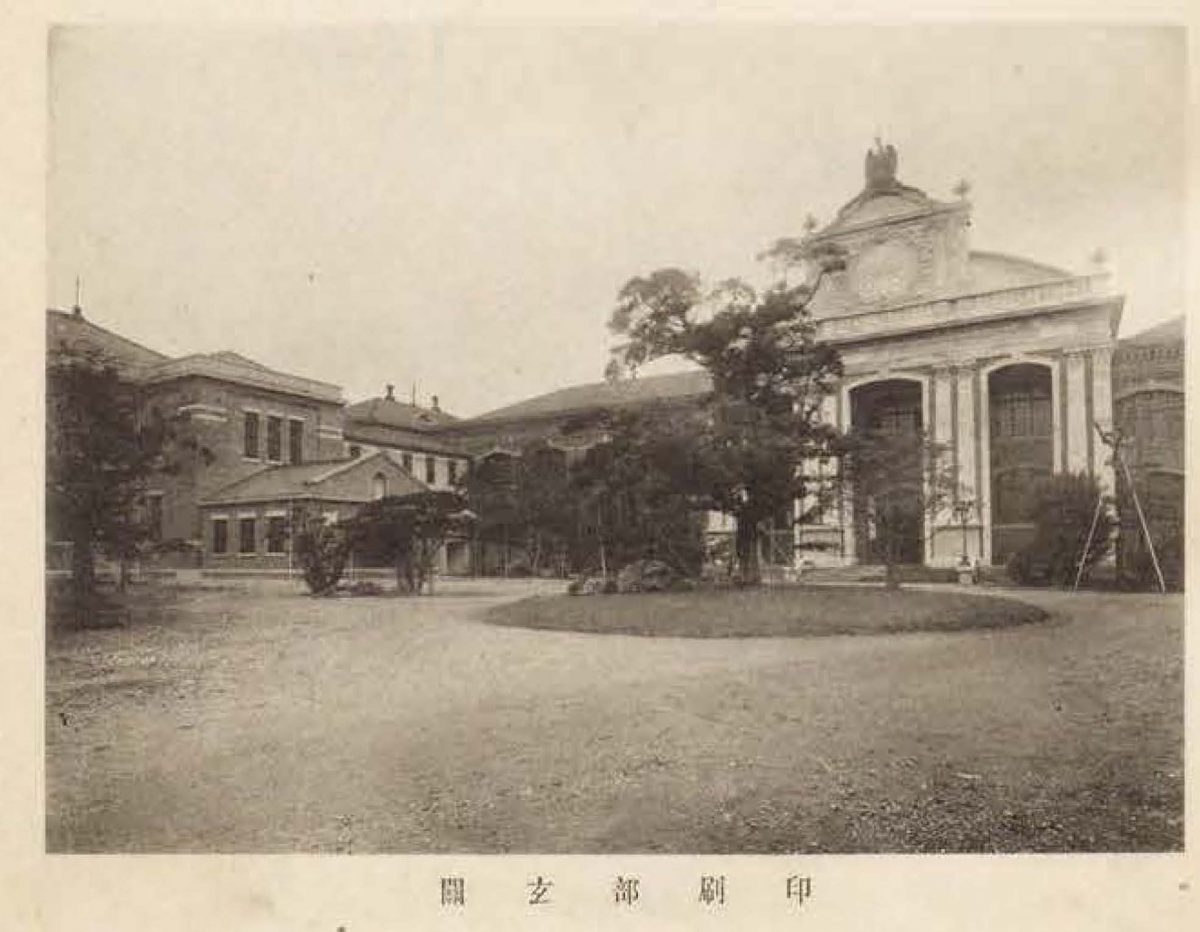

In 1921 the Tokyo Printing Bureau issued a commemorative volume celebrating its fifty years as official printer of revenue stamps, paper money and government documents. The history featured several photographs of the Bureau’s grounds and buildings. These were recycled as part of a set of promotional postcards issued contemporaneously, documenting the integration of the latest Western print technology within Japanese settings. The images were rather poignant in retrospect, offering a specific vision of modern technological application that would be lost in the Great Kantō earthquake and subsequent firestorm that devastated Tokyo and Yokohama in September 1923. The Bureau’s buildings and machinery were destroyed in the conflagration, and it took several years to rebuild at a new site.

The postcards document the Bureau’s manufacturing spaces, print machines and workers industriously labouring at relevant tasks in the printing cycle. They also provided visual contexts for floorplan details reproduced in the firm’s history.

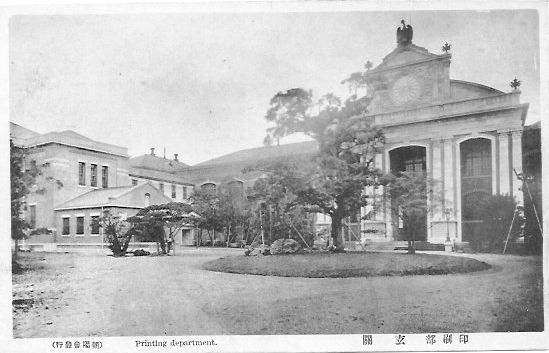

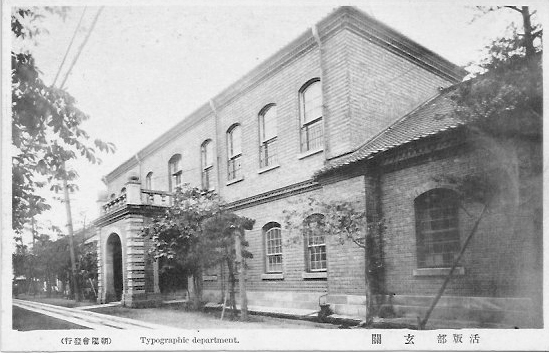

The firm’s official history had featured several images of building exteriors, including photographs of the driveway entrance to its main printing office and the entrance to its typographical department.

These images were reshot at closer, cropped angles, and reproduced in the contemporaneous set of picture postcards.

The exterior views served to contextualise the printing bureau buildings within local landscapes. The main office entrance had been built in baroque style, with three archways framed by a giant gable decorated with an imperial chrysanthemum emblem. The typographical department featured an arched entrance built within a large two-story brick structure, punctuated by large sash windows enabling light to enter workshop spaces. The grounds and buildings featured local foliage and cherry blossom trees, completing the siting of modern building facades within Japanese herbacious spaces.

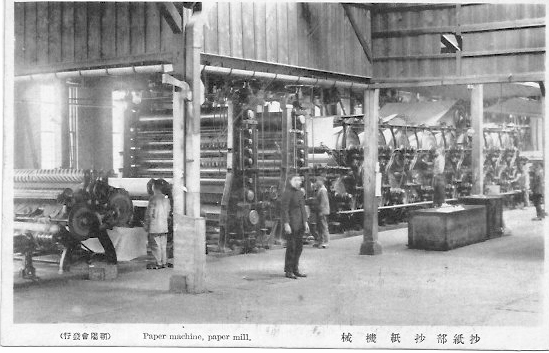

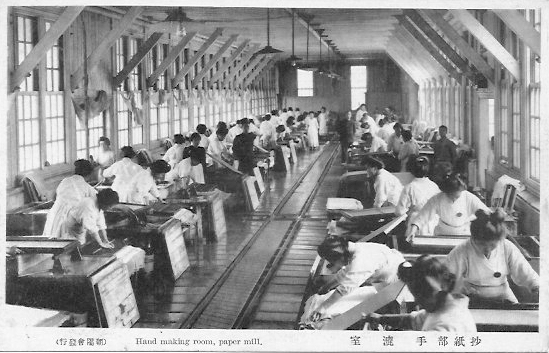

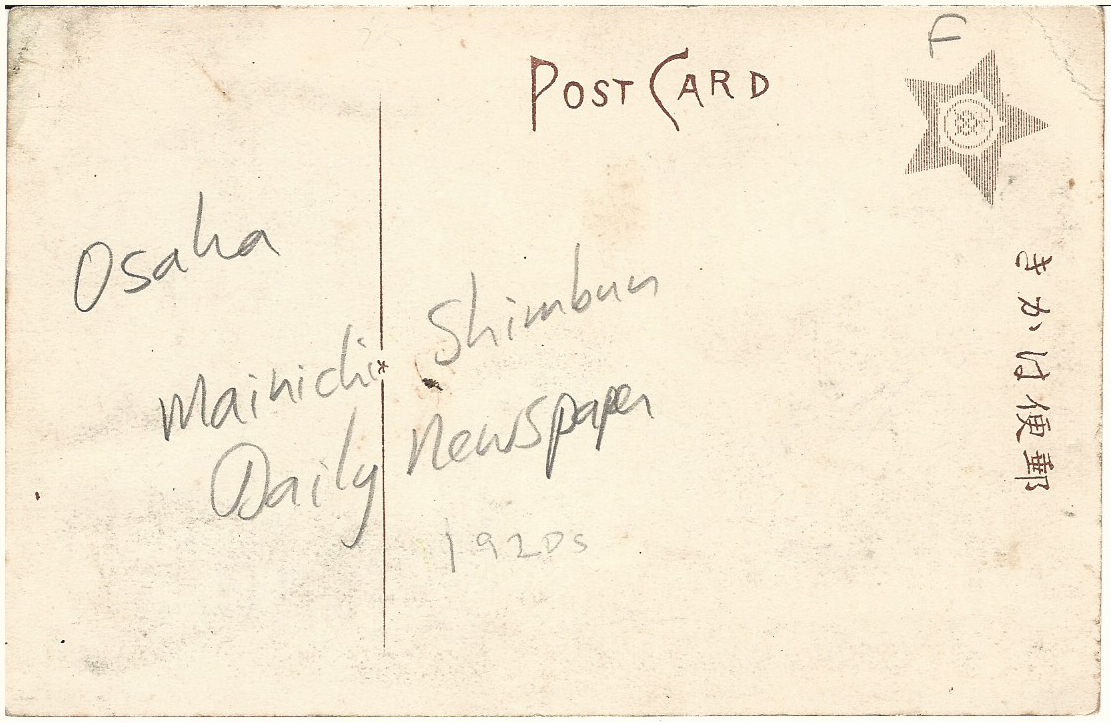

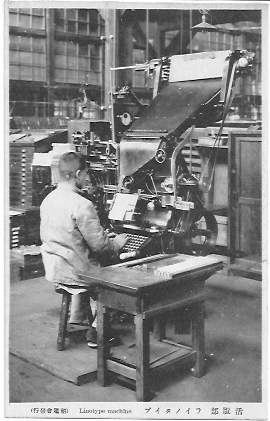

Other postcard images in the set included shots of male and female workers undertaking relevant industrial tasks, such as typesetting complex material, running printing machines, sorting paper, bundling finished postcards, and individual shots of complex ink, papermaking and printing machinery. The images were accompanied by scripts in Japanese and English describing what was represented in the postcard, such as ‘The Typographic Printing Room’, ‘Power plate printing room’, the ‘Mitsumata preparation room’.

Postcard images of the Imperial Bureau’s internal spaces featured adaptations of industrialised factory approaches to mechanical tasks. They proffered visual commentary on the use of modern technology to produce work of national significance. Japanese workers were presented in large interior spaces configured like stage sets, arranged in set spaces and undertaking set tasks. Management offices were not featured in these images. Instead, the postcard set outlined posed examples of men and women productively engaged in machine-based tasks leading to finished products. Captions were succinct, explicating the utilitarian functions represented in the postcards. Juxtaposing this documentation of technological shifts was a significant framing of such work within traditional contexts. Male workers were photographed wearing traditional tunics and cotton trousers as industrial garments suitable for shift work, with an equal number of female workers photographed in kimonos and hair pinned up in traditional form. All sported slip-on footwear adapted for the Japanese climate and working conditions.

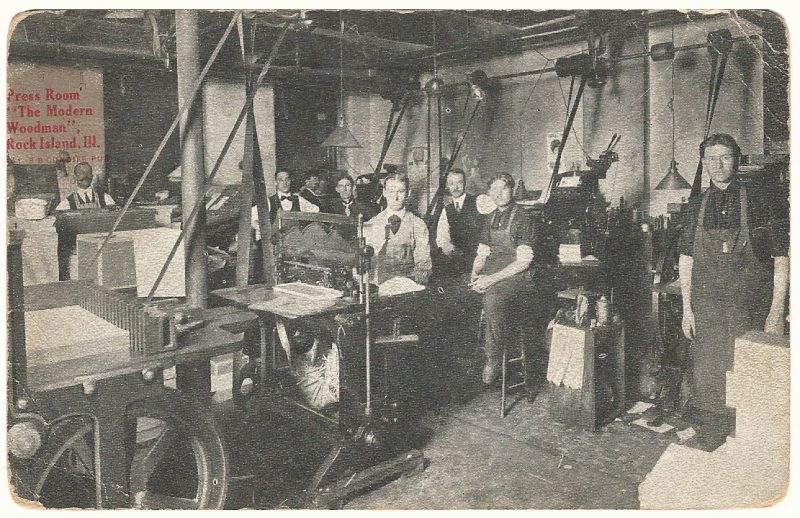

Such images had much in common with similar postcard reproduction of print spaces in other parts of the world during the same period. French, US and Japanese press and typesetting rooms represented workers uniformed in ways that reflected different national modes of dress. Nevertheless, the representation of interaction between workers and machines proved remarkably similar in intent.

Equally important regarding the Imperial Printing Bureau postcards were the links between the cultural and social uniqueness of the Japanese workspace and the firm’s absorption of new technology. Tradition was shown intertwined with new ways of working, as these images frequently reminded us through the juxtaposition of modern machinery and buildings with indigenous clothing and landscapes.

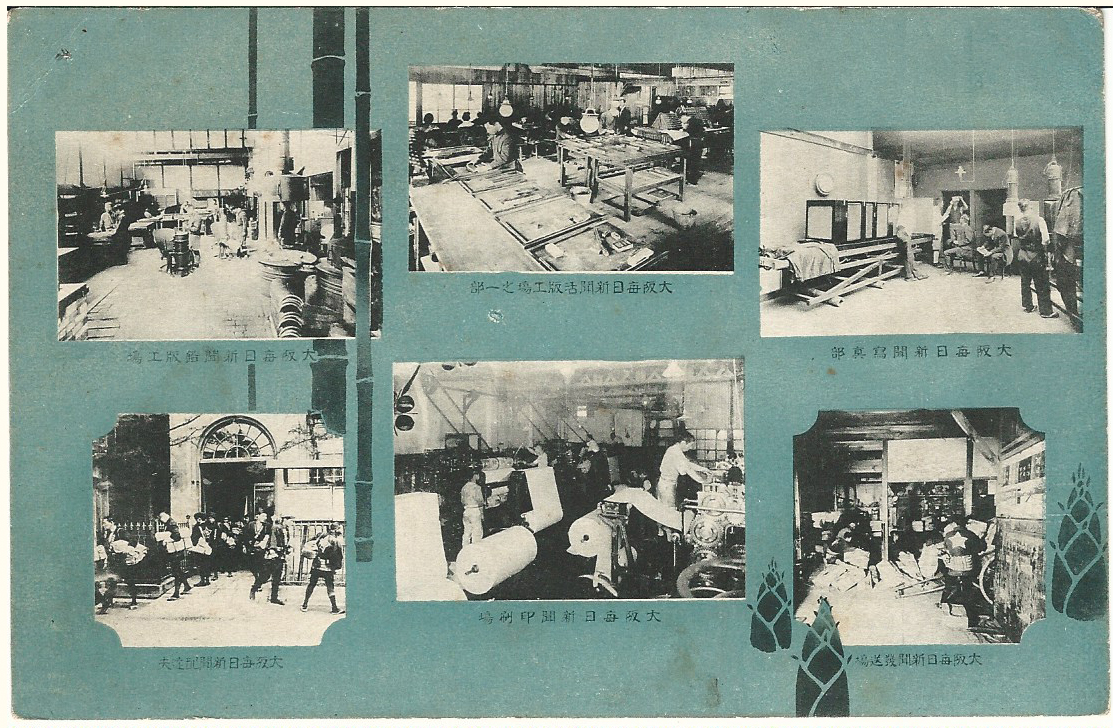

In contrast, a rare contemporary representation of business operations in the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun commercial newspaper sets an alternative vision of print modernity The 1920 picture postcard of Osakan press activity presents a tableau montage of different stages in the newspaper’s production: images of workers in nondescript industrial overalls and garments churn out the paper in crowded spaces, and the finished product is rushed out the door by young, smartly suited couriers eager to distribute the news of the day. The photographic images show Japanese print capitalism in a full embrace and appropriation of a modernity clearly shaped by Western influences. At the same time, the postcard interweaves bamboo shoots into the photo montage, fusing West machine and factory processes with traditional Japanese aesthetic.

These images are powerful starting points for considering intersections between print advertising, print culture and visual culture. Such postcards were used as powerful advertisements for documenting official print industries marching to the relentless beat of modernity. The Imperial Printing Bureau postcards open a window into the self-promotion of an agency upholding Japanese work traditions while simultaneously embracing new technology. It showed an organisation engaged in balancing between traditional work cultures and technological change. Pride and patriotism made their presence felt in the use of a democratic technology that embraced a modern identity but was also adjusted to Japanese cultural frameworks. Here, we also see a national institution positioning itself within consumer culture through the use of postcards as a means of advertising its activities.

Such postcard examples of print workplaces served to mark specific points in time, and document important collisions between visual culture and global creative industries. I intend to dig away further at their meaning. I am curious to unpack how the visual representation of space, skill and workers becomes incorporated into the compact space of a postcard. What can we learn from these surviving physical mementos about advertising, self-representation and creative artisanal and cultural identity? Of course, I continue to scour online sites in hopes of uncovering and acquiring yet more postcard examples like these. Perhaps the next one will reveal even more about the what, why and wherefore of industrial workplace representations.